|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disclaimer: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Improved

Specificiations for Federally Procured Ruggedized Manufactured Homes for Disaster Relief in Hot/Humid Climates |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stephanie

Thomas-Rees, Subrato Chandra, Stephen Barkazsi, Dave Chasar and Carlos Colon Florida Solar Energy Center |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Abstract Before reconstruction can begin after a natural disaster, temporary housing is essential to stabilization of a community. The offsite, rapid construction, and the ability to transport (and relocate) are two advantages of the ruggedized manufactured home. Two improved specifications, EnergyStar (ES) and the Building America Structural Insulated Panel (BASIP) manufactured home, are suggested in this paper that enhance the energy efficiency, sustainability, and indoor air quality and provide back up power, without compromising human health, safety or comfort. The energy performance of the ES and BASIP manufactured homes are compared to the base case or currently specified ruggedized manufactured home using the FSEC developed ENERGYGAUGE® USA (Version 2.5.9) software. The specifications presented in this paper allow for better quality construction and includes renewable energy. This not only reduces utility bills during regular operations but provides electricity and hot water for essential functions during power outages associated with reconstruction following a natural disaster. Introduction Hurricane Katrina caused major devastation to parishes, communities and entire cities requiring accommodations of mass quantities and extreme urgency. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) responded to the temporary housing needs by procuring over 100,000 travel trailers and over 25,000 ruggedized manufactured homes. However, finding the proper location and the costs associated with constructing, transporting, installing, maintaining and operating these temporary housing accommodations has become controversial. Local governments denied installments within flood zones (which are where most of the destruction and devastation occurred and where the temporary housing was needed) and local citizens brought opposition citing that they feared these “FEMA Cities” would increase crime rates and lower their property values. Critics believe that dispersing the money they spent per home, directly to each of the victims they provided accommodations to, is a better use of taxpayer dollars than purchasing these units for temporary and often, one time only, use. While the temporary housing program is antiquated, it is what the law allows. FEMA procured manufactured homes are used to accommodate victims of natural disasters. As hurricanes are predicted to intensify and increase in numbers, more temporary structures will be needed. When Hurricane Katrina struck the shores of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama last year, 25,000 manufactured homes and 100,000 travel trailers were ordered (and built) to help accommodate the thousands of victims who could not find and/or afford safe housing while their homes were being repaired or in some cases, rebuilt completely. By extrapolating information from recent articles, the costs associated with recent manufactured home and travel trailer purchases amounts to approximately 2.9 billion dollars. Each travel trailer costs about $10,000. Each manufactured home costs about $76,800 per dwelling, which includes purchase, transportation, installation, maintenance, cleaning and disposal. However, these figures do not include energy costs and environmental impacts, associated with the manufactured homes that are currently used. Continued to be scrutinized for temporary home expenditures, FEMA is complying with what law allows. The Stafford Act limits the amount of money FEMA can grant directly to an individual at $26,200. While this may seem like adequate funds to support a household for a period of 18 months, some times, as experienced during Hurricane Katrina, safe housing accommodations are not available because an entire community has been devastated. The program for providing ruggedized manufactured homes was developed in the 70’s and although antiquated, the program or procurement specifications warrant improvement. Manufactured homes, utility expenses, maintenance, etc. are provided at no cost to the victims until they can move back into their existing homes or find other permanent housing. The manufactured homes are typically provided for a period of not more than 18 months. Once the 18 month period has expired, the manufactured homes are vacated and immediately transported to a staging area for future reuse or sale through the GAS website (http://gsaauctions.gov/gsaauctions/gsaauctions). If displaced residents can not find affordable housing, extensions are granted by FEMA. Most recently, the Punta Gorda, FL village has extended the remaining occupants’ stay until September 2006, totaling a 24 month housing period for these residents. In Florida there are 4,160 manufactured homes or trailers still occupied by storm victims, down from a 2004 peak of more than 17,000. There were 551 families at one time in the Punta Gorda village that opened in November 2004 (see photo of typical FEMA temporary community, the one pictured in Figure 1 is in Arcadia, FL). The procurement process that FEMA initiates when manufactured home orders are needed, start with FEMA requesting quotes from manufactured home builders to build the homes in accordance with HUD Manufacturing Housing Standards, also known as Title 24 (Chasar, et al. 2004). The manufactured homes specified to these standards, developed in the 70’s, are often constructed to the minimum standards, resulting in large energy use compared to their site built equivalents. The specifications recently used in hot and humid climates (i.e. areas where Hurricane Katrina struck) have the potential for indoor air quality and high maintenance concerns, in addition to high energy use. Poor indoor air quality can induce medical complications in occupants with asthma or other chronic illnesses and with energy costs on the rise, procurement specifications necessitate energy efficient solutions without compensating human comfort or safety. If FEMA’s current procurement process is to remain standard procedure, this report recommends two specifications for consideration. The EnergyStar Ruggedized Manufactured Home (ES) and the Building America Structural Insulated Panel Manufactured Home (BASIP) specifications, included in this report, provide improved temporary shelter accommodations suitable for multiple moves, and have capabilities to provide power for essential loads during extended power outages. Not only are the tangible benefits associated with energy cost savings the justification for this report, but indoor air quality plays and increasingly demanding role amongst occupants with sensitivities to asthma and other environmental related health conditions. Also included in this report are energy cost comparisons and analysis.

Figure 1. FEMA City, Arcadia, FL The ES manufactured home specification is modeled from the Energy Star guidelines for manufactured homes (MHRA 2003). An ENERGY STAR labeled manufactured home must be at least 30% more energy efficient in its heating, cooling and water heating than a comparable home built to the 1993 Model Energy Code (MEC) (Chasar, et al 2004). The specification for BASIP goes a little further in creating a specification that results in optimal indoor air quality, increased energy savings and also provides “free energy”. Table 1 summarizes the window, and surface U values as well as other characteristics. Table 1. Summary of Construction

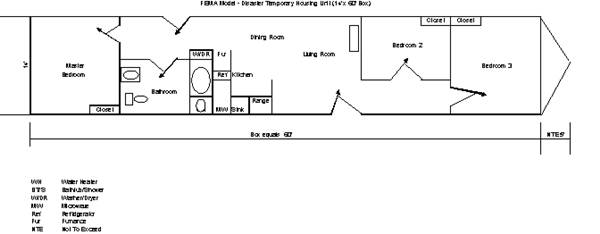

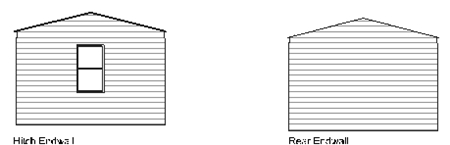

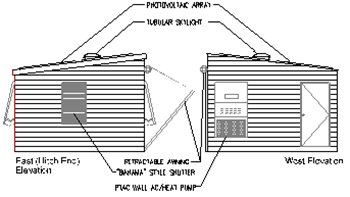

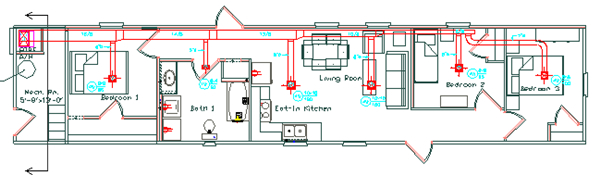

of the Existing and Proposed

*Figures from measured data of blower door test of US manufactured housing (Baechler, et al, 2002) Base Case, Energy Star and Building America Structural Insulated Panel Manufactured Home Characteristics Improving the construction methods and energy efficiency of federally procured ruggedized manufactured homes, used as temporary accommodations, will increase the durability and expand the life expectancy and reusability. The improved specifications and revised roof layout of the BASIP will also accommodate a mating of “single wide” units to make a “double wide” and larger unit that would provide a more comfortable environment and a more mainstream approach to typical home floor plans (see end wall elevations as illustrated in Figure 3). This report does not explore floor plan redesign at this time; however it does identify some of the few designs that have evolved since Hurricane Katrina left so many victims homeless. The base case or currently procured and the proposed ES ruggedized manufactured home have overall dimensions of 14’x 60’ (Figure 2). The units specified have 3 bedrooms and 2 baths. The base case and ES units have ventilated attics and gabled roof plans (Figure 3). The BASIP unit has been lengthened to accommodate a mechanical room and mono-sloped roof (Figures 4 & 5). The ES specification uses an advanced framing method. While the base case uses typical 2x4 stud construction spaced on 16” centers, the advanced framing method uses 2x6 studs spaced on 24” centers. Advanced framing methods may reduce wood use up to 25% and improve wall thermal resistance values from 5 to 10%. It can also decrease labor with fewer pieces going together, therefore saving money. The BASIP specification uses structural insulated panel method with integral wire chases for walls and the roof but the floor system uses advanced framing method, locating the plumbing requirements in the “belly”, as does the base case and ES. The BASIP specifies a photovoltaic (pv) integrated metal roof system with a skylight and Integrated Collector Storage (ICS) solar hot water system. The elevations illustrate “Bahama” style shutters that provide hurricane protection and solar shading. The end wall elevation (Figure 5) illustrates the inclusion of a retractable awning that also provides solar shading and additional square footage. Energy Analysis Using EnergyGauge® The proposed specifications and the base case federally procured manufactured home are analyzed using the FSEC developed ENERGYGAUGE® USA (Version 2.5.9) software program. This program predicts building energy consumption using the DOE2 analysis engine with a user friendly front end that develops DOE2 input files and models that are more appropriate for residential building systems (Parker, et. al, 1999). An analytical model was developed for each of the manufactured home specifications. These models were essentially the same with differences only in the R-values in the various building envelope components, the duct leakage values, the heating and cooling equipment, fenestration properties and the integration of renewable energy sources, i.e. pv and solar hot water heating. The base case and ES are similar in geometry but differ in hvac systems engineering and hvac equipment location. Considering the energy costs alone, these specification recommendations facilitate significant utility demand reductions. During a 12 month period, the latest order of 25,000 FEMA specified ruggedized manufactured homes will consume about 250 GWh, which will cost the Federal Government approximately 32.55 million dollars (at $0.13/kWh). If these units were deployed to other areas like Hawaii, where utility rates are almost 44% higher, the government’s electric bill could cost over 46 million dollars. The ES, which proposes to improve the energy efficiency by at least 14%, would provide a savings of over 4.5 million dollars over a 12 month period. The BASIP, proposes to improve the efficiency by at least 78% (see Table 2). This equates to about 19.5 GWh of electricity saving approximately 25.4 million dollars. The ES manufactured home would eliminate approximately 23,500 tons of greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to removing 3,815 passenger cars and light trucks from the highway for one year or saving our reliance on 49,595 barrels of oil. The BASIP specification would remove approximately 119,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to removing 19,318 passenger cars and light trucks from the highway for one year or saving our reliance on 251,134 barrels of oil. Table 2. Summary of Comparisons of Simulated Savings

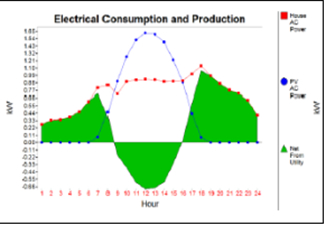

* Net Energy Usage = Total Energy Usage – PV Produced (see

Figure 7 for details)

Figure 2. Floor plan for the Base Case (Courtesy of Palm Harbor Homes)

Figure 3. Elevations for the Base Case (Courtesy of Palm Harbor Homes)

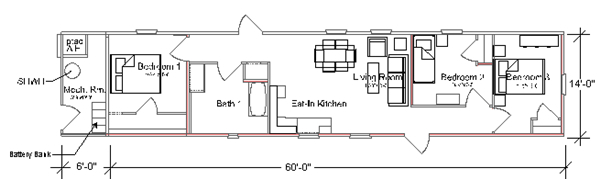

Figure

4. Floor plan (by Palm Harbor Homes, et al.) for the Energy Star

&

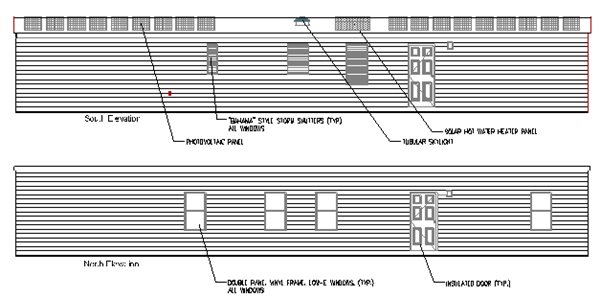

Figure

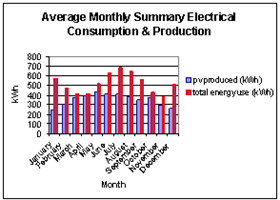

5. Elevations for the Building America Inegrated PV Array The BASIP specification proposes the integration of a 3.25kWp pv array that would generate the peak power requirements. This is especially beneficial when manufactured homes need to be deployed to areas where utilities have not been restored or during times when service is interrupted. EnergyGauge® models the annual energy use and the annual energy produced by the pv array for the home located in New Orleans, LA. Figure 6 illustrates the summary of monthly averages and Figure 7 illustrates the summary of hourly averages. The pv array produces a net energy of 4,224 kWh. Total consumption is 6,413 kWh annually for a net energy use of 2,189 kWh and 78% savings. If the pv array was omitted, the BASIP would produce 38% savings over the base case manufactured home.

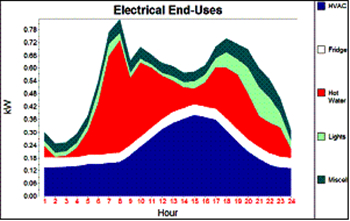

Figure 8 demonstrates the average hourly electrical uses for the whole year, revealing the hvac and hot water require the largest demand (which is also typical in the base case and ES models).

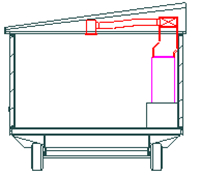

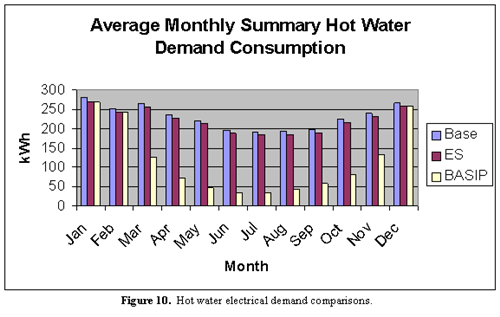

Figure 8. BASIP manufactured home HVAC The base case manufactured home as it is constructed today uses a mechanical system that is ducted under the floor of the home (referred to as “in the belly”). The air handling equipment is in the interior of the home and the compressor is set onto a concrete pad once the manufactured home is delivered to the site. This requires coordination and additional personnel to connect the system on site and also almost never involves any commissioning or verification that the system is functioning properly as designed. The ES manufactured home models an improved hvac system with higher energy efficiency and improved requirements on duct sealing. It also relocates the ductwork above the ceiling, as does the BASIP. However, the BASIP creates a conditioned space for the ductwork due to the sip system. The relocation of ductwork above the ceiling eliminates the risk of supply vents being covered with furniture. The BASIP uses the plenum above the ceiling and below the sip for return air supply (see Figure 9). This may create an example where innovative technology precedes code development because flame spread ratings and fire code issues may need to be investigated further to ensure code compliance. The BASIP specification proposes a hvac system that is installed onto the home in the factory, allowing the mechanical system to be completely operational upon delivery. The BASIP also properly sizes the unit with respect to its characteristics, allowing proper humidity removal and better indoor air quality. The energy savings from the improved air conditioning and heating demands amount to 44% and 45% for the ES and BASIP respectively over the base case. The BASIP can credit this savings so the increased energy efficient rating and the properly sizing of the system. The SIP, in addition to tight ducts, results in tighter construction, less leakage and better indoor air quality. Domestic Hot Water The BASIP manufactured home specifies an Integral Collector Storage (ICS) hot water system which saves about 50% energy over the base case and ES home (see Figure 10). In the ICS, the hot water storage system is the collector. Cold water flows progressively through the collector where it is heated by the sun. Hot water is drawn from the top, which is the hottest, and replacement water flows into the bottom. This system is simple because pumps and controllers are not required. On demand, cold water from the house flows into the collector and hot water from the collector flows to a standard hot water auxiliary tank within the house (Harrison, et. al, 1997). The benefit to using an ICS system over a drain back system is less mechanical parts and pumps. The BASIP unit will have a user’s manual and diagrams installed at the water heating system (located in the mechanical room, see Figure 3) that indicate freeze protection procedures during the months of December, January and February, as well as during transportation and relocation. Another benefit of using an ICS system is the availability of hot water during power outages.

Figure 9. BASIP cross section and HVAC Layout

Peliminary Economics Early in the research of this report, incremental cost estimates were generated for the ES manufactured home of about $900. However, due to the proposed wall mount hvac system, third party mechanical system installation costs are omitted (and for each relocation). These charges are estimated at $700 per move. Table 4 estimates incremental costs per component and assumes two moves. This results in a net savings of approximately $854 over the base case, including other proposed upgrades. The proposed BASIP manufactured home specifications have incremental costs associated with the skylight, pv, solar hot water system, high efficiency hvac system and sip construction. The pv array is a large incremental cost in the BASIP manufactured home specification. Systems can generally costs about $10K per kW of pv array. This would amount to approximately $32.5k for the specified BASIP system. Optimistically and with bulk pricing for many of these systems purchased, the array could be procured as low as $6 per kW or about $20k (the figured used in Table 3). Another large incremental costing component is the ICS hot water system. This is estimated at a $2,300 up charge from the typical electric water heaters, which cost about $200. The other incremental costs in Table 4 are likely much higher than would be actually realized due to the experimental nature of the proposal. With these caveats understood, Table 4 illustrates the incremental costs, energy savings and simple payback periods for each specification. The life cycle costs will be determined at a later date if the scope of this project warrants such investigation. Note that the savings and paybacks will vary in accordance with the home’s location in respect to the utility rates. Table 3. Incremental Costs Comparisons and Savings

Table 4. Component/Incremental Cost Estimates for ES & BASIP

Conclusions Through various programs that the federal government has initiated, the search for more affordable, energy efficient and sustainable temporary housing is taking a more aggressive stance in the building environment. When FSEC was tasked by DOE to develop a proposal for improved specifications for FEMA, we sought input from various industry partners to discuss different ways to improve the current FEMA specifications. This included manufactured home building personnel, material manufacturers, building science researchers and others. FEMA personnel was contacted on numerous occasions but declined to comment. These discussions along with several published reports formed the basis for the proposed recommendations in this report. One such published report was a site visit conducted by a member of the Building America Industrialized Housing Partnership and others affiliated with manufactured housing industry in September of 2004. The report discloses possible moisture-related problem areas and made recommendations for manufactured homes built for FEMA and destined for Hurricane Charley victims. The largest problem areas were the vapor barrier placement, duct leakage and oversized hvac systems (Chasar, et. al. 2004). In July of 2000 the first HUD-Code home made of structural insulated panels (SIPS) was tested, instrumented and monitored for energy efficiency (Baechler, et al., 2002). The results of this experiment provided the premise from which the BASIP was developed. The FEMA procured manufactured homes are currently constructed in accordance with the Housing and Urban Development’s manufactured housing standards (the HUD code). While there are many examples of high quality and cost effective manufactured homes, the FEMA minimum standard homes can consume more energy than their site built comparatives and use materials and mechanical systems that can potentially contribute to poor indoor quality and low durability. Two improved specifications are presented in this report to enhance energy efficiency, sustainability, indoor air quality and provide back up power, without compensating human health, safety or comfort, for high performance ruggedized temporary housing. Imagine the headlines revised from “The Land of 10,770 Empty FEMA Trailers” (Figure 11), to “10,770 Zero Energy Trailers Provide Power for Small Community”. If these units had been built with the BASIP specifications, they could generate enough power to provide basic power necessities of a small parish. With more and more headlines like “FEMA Homes Stranded in NC”, “Thousands Still Waiting for FEMA Trailers”; how does FEMA justify the process for temporary housing? Placing manufactured homes into communities affected by natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina has met enormous resistance by neighboring communities, as well as, local officials. “The NIMBY (not in my backyard) effect goes beyond the Big Easy itself: Half of Louisiana's parishes have banned new trailer parks”. The Punta Gorda FEMA Park (largest-ever trailer park) has received accusations about drug dealing, domestic abuse, theft and vandalism. Despite those concerns, some believe extraordinary events require extraordinary cooperation.

Figure 11. More than 10,000 trailers were sitting

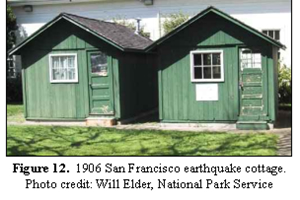

at the airport in Hope, AR The proposed specifications still need further investigation with regards to code exceptions and/or exemptions and fire resistance compliance due to innovative technologies that have evolved since the development and implementation of the HUD Code. Space planning and overall layout should also be examined further. While this report does not explore floor plan redesign at this time, it does identify a few designs that have evolved since Hurricane Katrina left so many victims homeless. Hurricane Katrina brought about many design charettes and discussions by architects, developers, politicians and manufactured housing executives. We can even look historically at measures taken after the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 left thousands homeless and over 5,600 “temporary cottages” were built (see Figure 12).

The consensus is that affordable, temporary housing needs to take on a new shape and mission. The U.S Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Department’s annual Solar Decathlon, a competition to design, build, and operate the most attractive and energy-efficient solar-powered home, displays examples every year of self sufficient innovative homes, that have been transported to the Mall in Washington D.C. Regardless, Hurricane Katrina has proved that a new process and strategy is in need, one that is healthy, sustainable, and reusable and before an energy crisis hits home again, and one that is energy efficient and responsible. References

Acknowledgement This work is sponsored, in large part, by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Building Technologies Program under cooperative agreement number DE-FC26-99GO10478. This support does not constitute an endorsement by DOE of the views expressed in this report. The authors appreciate the encouragement and support from Bert Kessler (Palm Harbor Homes), Bill Wachtler (Structural Insulated Panel Association), Bill Chaleff (Chaleff & Rogers, Architects), Janet McIlvaine (Florida Solar Energy Center), Danny Parker (Florida Solar Energy Center), Eric Martin (Florida Solar Energy Center), Dennis Stroer (Calcs Plus), Michael Lubliner (Washington State University), Michael Baechler (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory), Mike Dalton (Polyfoam), Ron Sparkman (Barvista Homes), John Michael (ATEX Distributing). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BAIHP Home | Overview | Case Studies | Current Data

Partners | Presentations | Publications | Researchers | Contact Us

Copyright © 2002 Florida Solar Energy Center. All Rights Reserved.

Please address questions and comments regarding this web page to BAIHP Master